The Cost of Privacy

Michael Trey Blackburn

November 9th, 2017

It’s no doubt that with recent advancements to how we live our day-to-day lives that we are truly living in the golden age of technology. What used to take uncertain amounts of time can now be accomplished in a matter of seconds, either from a computer, or even from the convenience of your cellphone, and it’s all made possible by the Internet. With sites and apps such as Facebook, Google, or Snapchat, one can share their life with family, friends, or even the entire world through status updates and pictures, but at one cost to the user? If you haven’t already taken notice we also live in a time where one may think that what they say and do online may be private, or for certain eyes only, but no matter how secure one may think their privacy online is, no one can be 100 percent private while using the Internet. The purpose of this blog is to look further into specific events and situations where privacy online has been invaded in some form or fashion, and at what cost.

History of Privacy

Privacy in the context we think of today, at least in the United States, has only been a topic of interest for a little over 100 years, whereas prior to that not many people were engaged in privacy the way we are today. Even when the United States was first founded the only thing that slightly resembled a right to privacy in early documents was the, “Fourth Amendment’s prohibition of unreasonable governmental searches,” (Goldsborough, 2010). An early example of when concerns over privacy began to appear goes back to the late 19th century invention of the telephone. When thinking about phones back then one wouldn’t think privacy would be a huge concern, but there were, in fact, some people who thought that having telephones in the house would be an invasion of privacy. According to author Carolyn Marvin, questions that people back then had over privacy concerns with the telephone included, “How would family members keep personal information to themselves? How could the family structure remain intact? What could be done about the effects of new forms of publicity on family intimacy,” (Marvin, 1988). Some people had these concerns, because they thought that personal and private family practices, such as a family dinner, would be interrupted by having a telephone. It may seem silly to think about that now, but with what we’ve had going on in recent times involving the Internet, privacy has definitely not become a laughing matter.

(DonkeyHotey, 2011)

Even in the early stages of the Internet some individuals were worried about being tracked and having their privacy invaded. Take for example the case involving the Olivetti Research Lab and their active badges. In the early nineteen nineties ORL issued devices called active badges to their employees to wear while working. According to authors Dourish and Bell, the active badge was a, “Small, wearable device that transmitted a unique infrared signal every ten seconds to a network sensor, which could then accurately identify the transmissions and so pinpoint the device’s location,” (Dourish & Bell, 2011). ORL thought that by issuing these to their employees it would assist the receptionist at the front desk with forwarding calls to whoever was needed on the line to speak with. Although the intentions were good, many employees thought this was invading their privacy when visiting areas, such as the breakroom or the bathroom. Later on, other companies who incorporated the badges also used them to collect data for certain research, so by refusing to wear the badge it would have an incorrect influence on the data. Due to this, the concerns of privacy over the badge turned into a bit of a moral issue. The big question became, “Do I wear the badge so that they can accurately collect their data, or not wear it and have their data become incorrect?”

Current Privacy Concerns

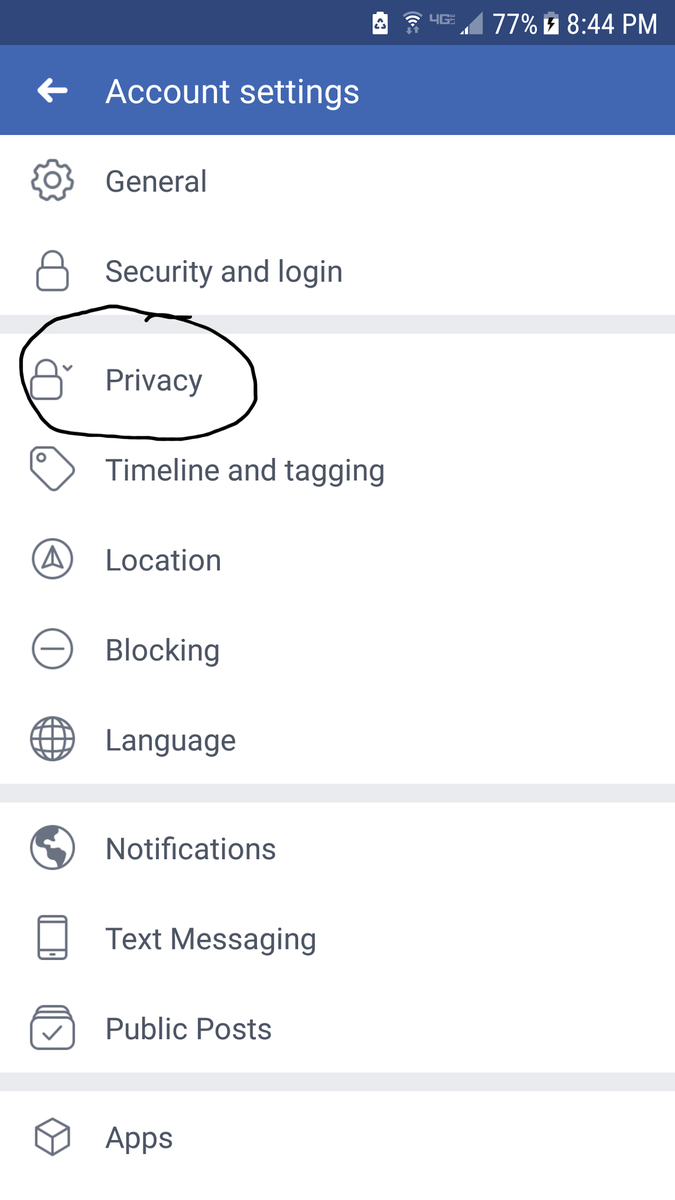

I think it’s safe to assume that the vast majority of those who read this blog have had, or currently possess an account on one of the most popular social media sites, Facebook. Facebook has undergone massive changes in its thirteen-year run before becoming the social media giant it is today. If you were to go into your Facebook settings right now you could have the option to make either different parts, or even your whole profile private, making it to where others who aren’t part of your friends lists unable to view certain things on your profile; such as your age, birthday, phone number, or even what you post; however, as of 2010, unless you had previously set up your profile to be completely private, Facebook has made it to where the default for your profile makes it 100 percent public to everyone who comes across it (Evans, 2010). This means that if one were to make a brand-new account all their information they list on their profile would be open for other users to see by default. As bad as that may sound it’s not the first time Facebook has come under fire for privacy issues with its users.

What is Happening?

Even with everything being completely private on your profile Facebook has still been

(Trey Blackburn, 2017) (Trey Blackburn, 2017)

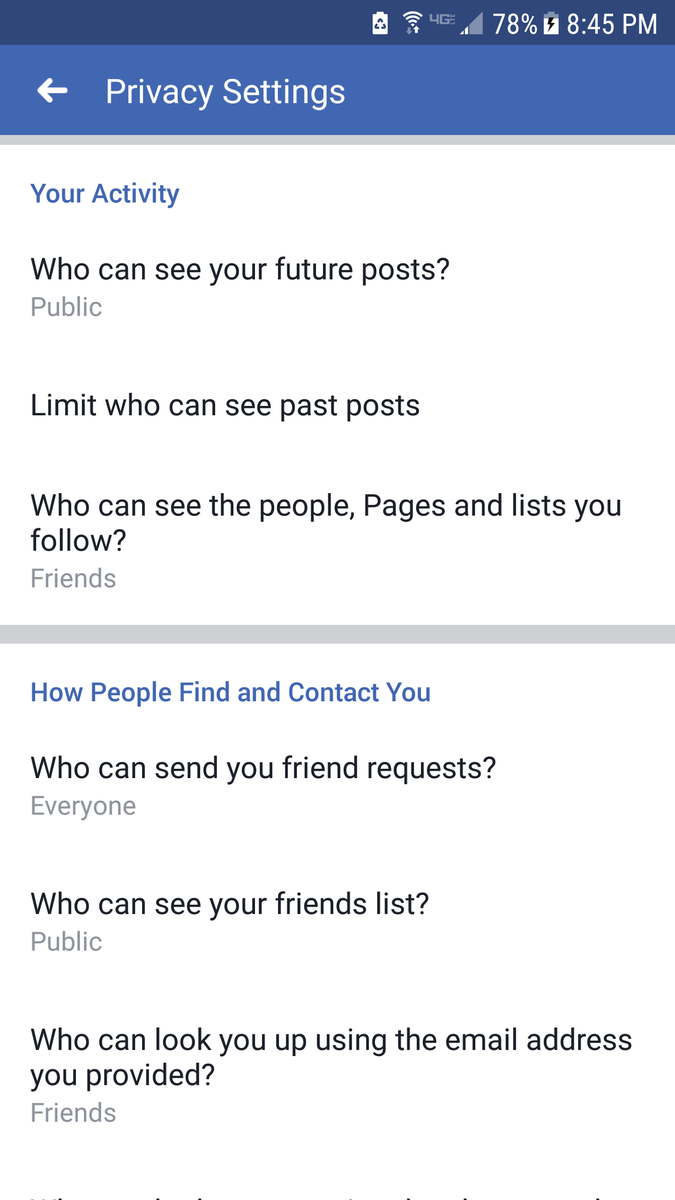

accused of violating the privacy of users. Because Facebook allows having a profile for free their

(Trey Blackburn, 2017)

revenue comes from generating ads, which can always be seen when using the social media site. Just this year, Facebook made more than nine billion dollars in ad revenue (Swant, 2017), and the numbers continue to grow every day, but it’s how some of those ads came up on your news feed that’s been stirring up a lot of controversy. For example, “If a Facebook user researches a new television on an external website or inside of a mobile app, their profile might now indicate an interest in televisions and in electronics, making it easier for advertisers pitching electronic devices to reach that user on Facebook,” (Oreskovic, 2014), meaning if you’ve ever searched for anything on Google, such as restaurants in your area, recipes, or even specific brands of clothing, Facebook has the ability to take what you searched for and provide you with advertisements based on those searches and label them as interests, thinking you’d want to see them. By doing this many users have expressed their displeasure and disapproval, because they believe that by having the ability to see what they’re searching online on other websites, Facebook has invaded their privacy by using users’ search histories as a means of generating ads and increasing their revenue.

What Sites are Doing

The category of advertising that sites like Facebook have been doing is known as behavioral advertising, which, according to author Madan Lal Bhasin, is, “A form of online advertising, is delivered based on consumer preferences or interest as inferred from data about online activities,” (Bhasin, 2016). As mentioned earlier, some sites can gain access to things one has previously searched for online, whether it be from Google, Pinterest, or some other website, and use those searches to feed the consumer ads based on what they searched for. According to Bhasin’s article, the revenue that comes from behavioral advertising is what allows websites to allow free services at no charge for the consumers. Many websites that participate in behavioral advertising would have to start charging consumers to use their services if they did not sell their information. Because the term “free” is so appealing to most people, and we can be honest here and say we as humans enjoy things that are free, online users are often willing to allow websites to sell their information to keep services free, which I will go further into detail about in the next paragraph.

Can They Do That?

It sounds shocking that sites like Facebook have been able to get away with acts such as the ones mentioned above, but sometimes there are circumstances where Internet sites are well within their legal rights to do so, and it’s because you gave them permission to be able to. Anyone who has spent enough time on the Internet or has signed up for some kind of service has come across a lengthy privacy policy, which we often skip over completely without giving it a second look and confirming at the bottom that we read the policy in its entirety and that we agree to its terms and conditions. According to a study conducted in 2015, as mentioned by author Charles E. MacLean, “65% falsely believed that if a company has a “privacy policy,” that means the company will not share consumer data with others without consumer permission; 64% wrongly believed that clearing cookies on a cell phone prevented marketers from tracking the user,” (MacLean, 2017). Based on this data and from the reading, most companies that include a privacy policy know already that consumers are going to willingly agree to the policy, because the consumers believe that by giving up certain rights of privacy they’ll be able to maintain a free online market, even though it gives the companies the right to sell their information to other markets. Similarly, to the case with Facebook mentioned earlier the information that is given to other online markets goes towards ads as a means of generating revenue. In other words, if consumers believe that a free market will exist, they’ll continue to give up confidential information in order to keep things the way they are.

(Youngson, n.d.)

Conclusion

It’s become clear that many people who use the Internet are having their privacy invaded, but at the cost of being able to use free services. People nowadays are willing to give up personal information if it means they don’t have to pay for something. All of us have seen the typical privacy policy when signing up for something, and very few of us actually read the entire policy. As a result, we gain a free service, but in return we give up our privacy so businesses can sell the information for ad revenue. The way it looks, as long as people are willing to give up their privacy, many Internet services will remain free.

References

Bhasin, M. L. (2016). Challenge of guarding online privacy: role of privacy seals, government regulations and technological solutions. Socio-Economic Problems & The State, 15(2), 85-104.

DonkeyHotey. (2011, June 9). If It’s on the Internet, It Isn’t Private. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/donkeyhotey/5816482161

Dourish, P., & Bell, G.(2011-04-22). Rethinking Privacy. In Divining a Digital Future: Mess and Mythology in Ubiquitous Computing. : The MIT Press. Retrieved 28 Nov. 2017, from http://mitpress.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.7551/mitpress/978….

Evans, J. (2010, December 30). Top 5 Privacy Violations of 2010. Retrieved November 10, 2017, from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/jeffrey-evans/top-5-privacy-violations-_b…

Goldsborough, R. (2010). Are You Protecting Your Privacy Online?. Teacher Librarian, 37(5), 72.

MACLEAN, C. E. (2017). IT DEPENDS: RECASTING INTERNET CLICKWRAP, BROWSEWRAP, “I AGREE,” AND CLICK-THROUGH PRIVACY CLAUSES AS WAIVERS OF ADHESION. Cleveland State Law Review, 65(1), 43-57.

Marvin, C. (1997). When old technologies were new. Oxford University Press.

Oreskovic, A. (2014, June 12). Facebook Is Now Tracking You Even More Closely For Its Ads. Retrieved November 10, 2017, from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/06/12/facebook-ad-profiles_n_5487372…

Swant, M. (2017, July 26). Facebook Raked in $9.16 Billion in Ad Revenue in the Second Quarter of 2017. Retrieved November 10, 2017, from http://www.adweek.com/digital/facebook-raked-in-9-16-billion-in-ad-reven…

Youngson, Nick. (n.d.) Privacy Policy. Retrieved from http://thebluediamondgallery.com/privacy-policy.html