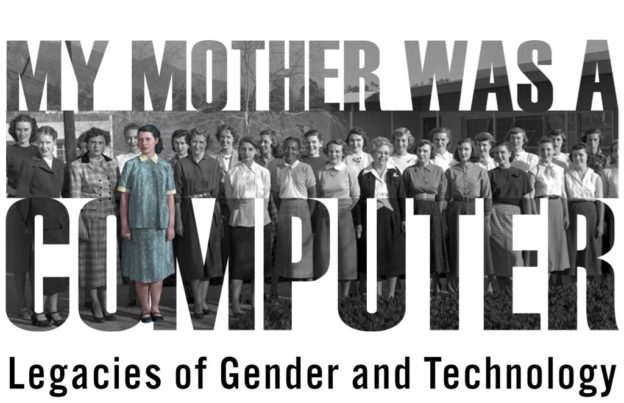

“My Mother Was a Computer: Legacies of Gender and Technology” was a one day symposium (November 2, 2018) at William & Mary organized by my professor, Dr. Liz Losh. The day was packed from start to finish with smart conversation, witty one-liners, and open-ended questions, many of which I will point to here. The symposium featured three panels (Gender and Programming, Gender and Gaming, and Gender and Online Community), an artist talk with Mattie Brice, Lightning Talks by members of the Equality Lab, and a stunning keynote by Dr. Wendy Chun.

One of the most interesting concerns raised from the Gender and Programming panel was the question of opportunity and empowerment. Dr. Janet Abbate spoke on the ways that we praise the talents of children learning to code, thus enforcing the idea that coding is somehow innate and must be fostered if the talent appears early, but Dr. Abbate reminds us that this is a skill that can be learned at any age. In terms of empowerment, Abbate spoke quite eloquently on the fact that we empower girls to code, but then what? Are the skills that we teach then to be used to serve a narrow demographic? How do we empower? Do we get women in the door and let them change from within or do we empower them as entrepreneurs? As someone with a particularly entrepreneurial spirit, I personally like the idea of providing women with skills to go forth and create their own path. As Audre Lorde says, you can’t dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools– we either need new tools or to move away from the house and construct a new one altogether. (Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.”)

In addition to Abbate’s concerns about opportunity and empowerment, Dr. Mar Hicks and Dr. Sarah McLennan both spoke about absences in the archives when it comes to finding diversity in the history of programming. McLennan discussed the importance of combing through African American newspapers for information about Black computers, because often those communities new about the work they were doing, and filling in the gaps from there, but Hicks points out that locating non-heteronormativity in the archive is so difficult because a lot of that information was simply not recorded at all.

Mattie Brice’s artist talk was one of the most intriguing aspects of the symposium. I appreciated the transparency with which she talked about her journey to being the game artist that she is– but within that title of artist is the work of an activist, as Brice spoke about wanting to create games that “did the work they said they were doing.” She wanted games that “changed things.” And again, a concern that recurred throughout the course of the day was this idea of Do I stay and change things or do I go? I personally struggle with that issue a lot, particularly being within the confines of the Academy, knowing that this system is not set up for Black women to succeed. (Or at the very least, it’s a system that puts up 500 more barriers between BW and success than it does for white men, but hey, that’s just my opinion.) Sometimes it is so appealing to imagine creating an entirely new path but then I think of my future students and I decide to stick this process out, for me and for them.

In the Gender and Gaming panel, one of the first and biggest questions raised by Dr. Amanda Phillips was, What happens if you center queer women of color in games? And then, Where are the moments of absence in games studies? Again, we circle back to these questions of absence– even in what I consider the most innovate fields of study, such as games studies, we always have to ask ourselves, who is absent and what do we do about these absences? Finally, Dr. Bo Ruberg asked the audience to reclaim “sloppy scholarship,” and what it would mean to do sloppy scholarship as a feminist enterprise. It incorporates the messiness of dealing with things that cannot be easily categorized and what is fluid. There is something so appealing to me about thinking of the ways I can free myself as a scholar, and engaging with “sloppy scholarship” is one way of doing that.

The last panel, Gender and Online Community was intense. From Dr. Dorothy Kim’s assertion that “If my mother was a computer, she was also probably a fascist and a white supremacist” to Alice Marwick’s work on online harassment. In all honesty, I’m still reeling from all the information and connections that I absorbed during that panel. I think most striking to me was Dr. Marwick’s comparison of online harassment to street harassment. It’s a spectrum: it can go from something as “seemingly benign” as telling a woman on the street to smile to full out stalker. I inherently know that the internet and having a public persona can be dangerous, but I am exceptionally lucky to have not been exposed to much internet harassment. My twitter community is as much home to me as my actual apartment. My internet friends are just as important to as my IRL friends. It scares me to think that there’s a potential for someone to destroy that positive internet experience for me through harassment. But it happens every day. Marwick points out that women who work on social justice enterprises are even more subject to this targeted harassment, and as a Black woman who does work on injustice and whose work is more and more becoming public, I now have a nagging fear in the back of my mind.

The day’s events concluded with Lightning Talks by members of the William & Mary Equality Lab: Jennifer Ross, myself, Sara Woodbury, Laura Beltran-Rubio and Jessica Cowing. I gave a talk on the Lemon Project: A Journey of Reconciliation and the digital humanities projects that I have worked on with Branch Out students in 2017 and 2018, as well as a preview of what we will be doing for the 2019 trip. I actually got a lot of positive feedback on my talk from some of the amazing scholars I’ve written about in this piece and so I think next time, I will take another step forward and present on some of my own personal work– maybe even a talk on Black Girl Does Grad School.

After a short break, we all reconvened for the evening’s keynote lecture by Dr. Wendy Hui Kyong Chun. What a spectacular piece of scholarship. She managed to weave together the personal and political with the historical and an unapologetic infusion of Korean language and culture. She began with the story of computing’s star figure Grace Hopper and her rejection of feminism and slid seamlessly into the story of her own mother, who was a keypunch operator. Chun spoke of the fact that English proficiency wasn’t required for a successful keypunch operator, only the ability to input data quickly and efficiently. She moved quickly from this lighthearted discussion of her mother and childhood, into a conversation around the Montreal Massacre, which happened during her second year of engineering school. In the chilling narrative, Marc Lepine killed fourteen women in the engineering program and the story around the massacre blamed feminists for the violence and hate, something that tweeters of the Symposium (particularly Adrienne Shaw) have identified as a recurring theme in many tech spaces.

As I reflect on this symposium, I return to the image of Chun’s mother as a keypunch operator. I think frequently of how I can weave my parents’ stories in to my own academic narrative because their stories intersect with my own. In order to adequately explain my interest in visual culture, it’s necessary to know that my father is a transportation planner, and I grew up with a drafting table and special blue pencils that I wasn’t supposed to play with (but did anyway) in our room over the garage. Because of him, I wanted to be an engineer– I went built popsicle stick bridges, drew my own highways and when I got older, built an electric keyboard at an engineering camp. It’s this love of making and building that I think draws me to the digital humanities, but you wouldn’t know that unless you knew my story, which is also my father’s story.

Wendy Chun gave me a model for combining the personal, the political and the historical in a deeply engaging and critical way and I thank her for that. In her talk, she prefaced it by saying she’d never done anything like that and may never again– but in the off chance she reads this, I hope she will. We need those stories.

My mother wasn’t a computer, but thanks to this symposium, I’m more interested than ever in these gendered legacies of technology. Many thanks to Liz Losh for organizing another great event.