WHY IT MATTERS WHO OWNS AND GOVERNS OUR GLOBAL CONNECTIVITY

If our networked tools for sharing knowledge are free, far reaching, and fast, does it matter who owns and governs them? I’m posting the draft of a chapter of my dissertation on the Humanities Commons in support of the belief that the infrastructure of knowledge production is in fact as important as the content of knowledge itself. Though freely-available virtual spaces such as Facebook, Google Docs, and Academia.edu enable democratic, open, and collaborative forms of knowledge production, their use simultaneously contributes to the power and intelligence of corporations that deny public understanding and oversight of their activities.

As Jonathan Taplin recently put it, “America is slowly waking up both culturally and politically to the takeover of our economy by a few tech monopolies. We know we are being driven by men like Peter Thiel and Jeff Bezos toward a future that will be better for them. We are not sure that it will be better for us.”

In a world in which everyday knowledge production actively contributes to the power and intelligence of tech monopolies, we need a new way for thinking about the holistic effects of our practices of making, sharing, and accessing information. Counter-intuitively, those effects may not always have much to do with the content of knowledge itself.

Longstanding assumptions about the objective nature of knowledge and its purpose have made it difficult to fully appreciate the way in which everyday networked communication directly supports the stronghold tech monopolies have on nearly every aspect of our world. My chapter shows how optimistic visions of the networked world—even long before its actual arrival—fail to anticipate how its economic foundations might undermine its promise.

Visionaries throughout the early 20th century such as Nikola Tesla, H.G. Wells, and Vannevar Bush foresaw the possibility of a globally-connected world and celebrated the democratic, intellectual, and practical potential of tools that could transmit great quantities of information instantaneously between any two researchers or even everyday individuals on the planet. In their enthusiastic realization that such connectivity would soon be technically possible, they considered information and its infrastructure in purely objective and positive terms. To their minds, global connectivity could have but one outcome: universal knowledge would flow ubiquitously and as a result human progress would ensue.

In line with these thinkers, contemporary scholars and commentators such as Yochai Benkler, Henry Jenkins, and Kevin Kelly have celebrated the ways that networks have supported participatory culture, democratized knowledge production, and aided the development of powerful forms of artificial intelligence that assist with everything from human well being to longstanding, difficult research questions.

The exciting achievements of networked activity should not be discounted, but need to be rethought given their role in an oppressive economic logic. As Google “takes over the classroom,” “corporate raiders” privatize scholarly research, the Federal Communications Commission threatens to eliminate net neutrality, open access education projects are appropriated for monetization, and data science turns education into a “pipeline for human capital management,” it is becoming increasingly clear the ubiquitous flow of information does not automatically translate into human progress.

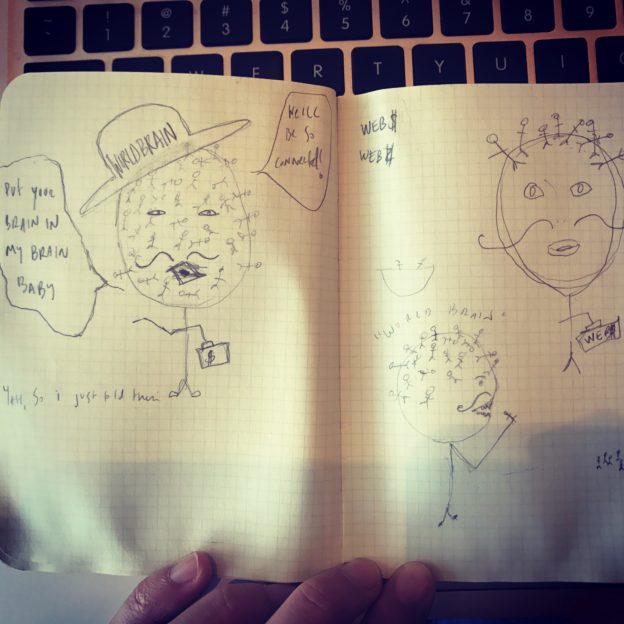

My chapter, “Alienated Intelligence: The Private Interests of the World Brain,” surveys the promises of networks as articulated by Benkler, Jenkins, and Kelly, and attempts to show how these promises are undermined by the economic conditions of networked activity. I catalogue their visions as part of the genealogy of what cyberneticist Francis Heylighen describes as the “global brain,” or a “metaphor for (the) emerging, collectively intelligent network that is formed by the people of this planet together with the computers, knowledge bases, and communication links that connect them” (274).

This global brain metaphor allows us to ask, what social body is our network serving? Whose intelligence is being produced by our networked activity? And what world is our knowledge making?

These are the humanistic questions of the age, and would benefit from the engagement of every discipline. Answering them, however, will involve more than just thought, but a thoughtful use of the tools we use to produce it. I’m proud to join the Humanities Commons in this urgent endeavor.

This chapter is part of a project I call #SocialDiss, in which I’ve committed to posting dissertation chapter drafts and reflections on different platforms for public review.