Abstract

“A Digital Reading of Twentieth Century Demography” brings the tools of the digital humanities to the history of demography, or population science, in the twentieth century. The project provides an overview of population science in the twentieth century, identifying the broad outlines and thematic trends of the field. “A Digital Reading of Twentieth Century Demography” examines and explores the demography scholarship, keeping the results open-ended so that different users could find their own implications.

Demography – the study of human population – acquired its own journals in the second half of the twentieth century, as public anxiety about global population grew and as private foundations contributed more money to the study of population and its control. Unlike population ecologists and population geneticists, who study non-human populations and tend to think that their findings could be generalized to human populations, demographers focus on things that are unique to human populations, that is, social, political, and economic influences on population change. During this period, demography scholarship increasingly focused on fertility and family planning, and demographers frequently published in journals specific to the new field of family planning as well as those specific to demography. Demography maintained its connection to family planning after the 1980s, and following this, fertility and family planning content comprised a smaller proportion of demography journal literature after that.

In “A Digital Reading of Twentieth Century Demography,” Assistant Professor of Science and Technology Studies at UC Davis Emily Klancher Merchant depicts the history of demography using the Data-Driven Documents (D3) JavaScript library, which generates visualizations – some of which are iterative – that represent data. Specifically, D3 generates scalable vector graphics that are embedded in web pages. HyperText Markup Language (HTML) structures the content on the pages in which the graphics are embedded and Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) controls their appearance. The project began as a supplement to her dissertation “Prediction and Control: Global Population, Population Science, and Population Politics in the Twentieth Century,” which investigates the reciprocal relationship between demography and population politics in the twentieth century. “A Digital Reading of Twentieth Century Demography” digs deeper into the science of demography and the its history between 1920 and 1984.

My first impression of “A Digital Reading of Twentieth Century Demography” was how different the topic modelling is from “Mining the Dispatch,” a similar project that uses topic modeling to examine a Virginia newspaper during the Civil War. This difference reflects the scope of each project. In the case of “Mining the Dispatch,” there are several graphs for each topic of one periodical. “A Digital Reading of Twentieth Century Demography” aggregates 30 topics into 12 themes so that there are only three charts, one for each periodical. “A Digital Reading of Twentieth Century Demography” viewers generally will not have to scroll as much as they will on “Mining the Dispatch” for this reason.

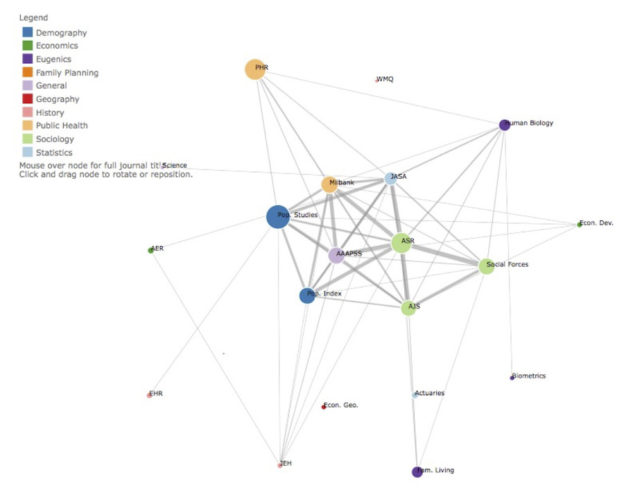

Another project that came mind when viewing “A Digital Reading of Twentieth Century Demography” was “A Co-Citation Network for Philosophy.” Both include a network analysis of a scholarly field. “A Co-Citation Network for Philosophy” depicts a co-citation network (see thumbnail), where articles are linked if they cite the same articles in their bibliography – a measure of similarity. “A Digital Reading of Twentieth Century Demography,” on the other hand, displays co-authorship networks, where people are linked if they published an article together, which was possible with the metadata Merchant had from JSTOR; co-citation networks were not. I found the co-citation network in “A Co-Citation Network for Philosophy” to be large and indigestible. There are 520 items on the graph and not enough space between them, so titles tend to overlap, thus deeming them unreadable. The co-citation network in “A Digital Reading of Twentieth Century Demography,” however, is small and spacious. The size of each node is proportional to the number of population articles published in a journal in the given decade, which prevents the commonalities seen in “A Co-Citation Network for Philosophy.”

Figure 1. Topic modeling on “Mining the Dispatch.”

More generally, the project contributes to histories of population thought and politics in the twentieth century. In, Fatal Misconception, Matthew Connelly, traces governments and nongovernmental agencies’ attempts at controlling population growth in the twentieth century vis-à-vis sterilization camps and selective breeding. Allison Bashford follows a similar train of thought in Global Population by using historical artifacts to map the world population problem that arose after the first World War and lasted for four decades – from the nineteen twenties to the nineteen sixties. Derek Hoff’s The State and the Stork looks at how the population problem influenced public policy and economic thinking, while Thomas Robertson’s The Malthusian Moment looks at how the population problem gave rise to environmentalism.

Merchant also adds to histories of demography such as those put forward by Dennis Hodgson, Simon Szreter, and Susan Greenhalgh, as well as to histories of the social sciences. Joy Rohde’s Armed with Expertise, for example, investigates the militarization of social research in America during the Cold War; Rebecca Lemov’s The World as Laboratory examines the precarious experiments of twentieth century social engineering.

Methodologically, the project is inspired by projects like Andrew Goldstone and Ted Underwood’s “What can topic models of PMLA teach us about the history of literary scholarship?” The project uses topic modeling to examine the content of twentieth-century scholarly journals.

Drawing upon data and information from a multitude of sources, “A Digital Reading of Twentieth Century Demography” becomes a central hub of the science of demography in the twentieth-century. Merchant is the first to use data visualizations to envisage connections among demography’s practitioners and among demography’s publications (I fact-checked this claim).

“A Digital Reading of Twentieth Century Demography” is a website with three sections, the first of which is titled “Population Association of America” (PPA). The first section provides historical context for the PPA, a non-profit professional organization for population scientists working in the United States. “Population Association of America” branches off into three subsections: PPA Presidents: Fields and Affiliations, PPA Intellectual Genealogy, and Discussion of PPA Analysis. The second main section, “Topics in Population Science,” gives an algorithmic reading of Population Studies, Demography, and Population and Development Review – twentieth century population-oriented journals. “Topics in Population Science” has four subsections: All Topics, Articles by Topic, Topics by Journal, and Discussion of Topic Analysis. “Networks in Population Science” is the third main section and consists of Journal Networks, Author Networks, and Discussion of Network Analysis.

Figure 2. Topic modeling on “A Digital Reading of Twentieth Century Demography.”

The website does not explicitly state who the other authors, editors, and collaborators were, as well as who funded the project, though Merchant clarified over email that there were no collaborators, which she acknowledged is rare because the digital humanities is often done collaboratively and on a large scale; she received funding from the University of Michigan.

The layout of the website is straightforward. The display is split in two. The content sits on the left; the title and navigation menu sit on the right. The navigation menu is vertical, which encourages the user to explore the sections of the website in order, beginning with “Introduction.” Most of the clickable information is contained within the navigation menu, but some of the maps displayed to the left of the screen have next buttons, and several words hyperlink to background readings, so the left side of the website occasionally contains paths.

Despite the user-friendly interface of the website, I believe that the research agenda of the project is limited to practitioners of either demography, history of demography, or the digital humanities, as it is specific to the field. A similar project that would have more widespread appeal is “Everything on Paper Will Be Used Against Me” by Micki Kaufman. This uses similar analytic methods to examine telephone conversations and written memos by Henry Kissinger when he was Secretary of State. This would appeal to a much wider audience, as people in many fields – history, political science, sociology chief among them – as well as the public are interested in Henry Kissinger. Conversely, the history of demography is a niche subject.

But Merchant states that she would like for the website to be used in conjunction with contemporary scholarship on twentieth century demography. Consequently, the project should appeal to researchers in the social sciences, as Merchant wants the project to be a tool for demographers and historians who want to know more about the history of the field of demography in the twentieth-century. The “Intellectual Genealogy” section and the “Author Networks, 1925-1934” section, for example, would be of particular interest to demographers. “Intellectual Genealogy” includes only demographers who were presidents of PAA or who trained as presidents. It indicates that about half of all PAA presidents come from the same intellectual lineage. “Author Networks, 1925-1934” shows who co-authored articles, which indicates who knew and worked with whom.

The content is static, HTML and CSS generated graphs and writing, the exception being the D3 models. Googling “A Digital Reading of Twentieth-Century Demography” yields three results from the University of Michigan, ResearchGate, and Digital Humanities at Dartmouth. But the Melbourne-based company SEO Centro’s analyzer revealed several issues within the website that, if fixed, could help it better circulate among Merchant’s desired audience.

The website received an SEO score of 44 out of 100 and a speed score of 60 out of 100. A few technical improvements would better help search engines like Google find, index, and rank the site. (1) It would be useful to add searchable heading tags to the index.html file (e.g. <h1>). (2) It could help to add an XML (Extensible Markup Language) sitemap to the to the source code to provide search engines with additional information, such as all the URLs associated with site, as well as temporal and priority information (i.e. which pages are most pertinent and have recently been updated). Several XML sitemap generators are available online free of charge. (3) A Robots.txt file would give search engine robots instructions for how to crawl and index the pages on the website. (4) It would be great if the website had a description so that users could read about the project in the Search Engine Result Page (SERP). The latter could be accomplished by adding <meta name=“Description” content=“Description about the page.”> to the <head> section of the index.html file. (5) The title tag of the website would benefit by matching the content on the webpage (e.g. SEO Centro gave the title relevancy of the website a 14% for this reason). (6) The website would receive its due respect in the search engine results by having a title no longer than sixty characters, as search engines are truncating the current title for being 64 characters long.

Figure 3. The massive co-citation network of “A Co-Citation Network for Philosophy.”

The optical character recognition (OCR) is not available because it is proprietary – owned by JSTOR. Nonetheless, the encoding of “A Digital Reading of Twentieth-Century Demography” is open access. Developers and scholars could inspect the page to see the source code to either improve the website or analyze and tweak the source code for their own endeavors.

“A Digital Reading of Twentieth-Century Demography” resonated with me. The project does not synthesize information that was already available; it produces new information by looking at all of the scholarly literature as a cohesive unit and examining the similarities and differences, as well as the connections. One of the interventions that Merchant was trying to make is to show that demographers were closely associated with the new field of family planning, which emerged shortly after demography with some of the sources of the same funding, but that the two were indistinct. I think she was successful.

I am not sure that the project itself has larger implications, but I trust that it can serve as a foundation from which to identify larger implications. Merchant mentioned in an email that the point of “A Digital Reading of Twentieth-Century Demography” was to examine and explore the demography scholarship, keeping the results open-ended so that different users could find their own implications. The project not only helped Merchant make important insights into the history of demography that she has argued at greater length elsewhere, but it also serves as the basis for an article that will be coming out next month in Population and Development Review, where she will argue that demography’s funders were fundamental to the establishment and development of the field, and that they helped focus the field on the issues of importance to them, such as fertility and family planning. She discovered the surprising lack of attention to the environment in the field of demography through topic modeling. The network analysis – journal networks – helped her track the development of demography as an interdisciplinary field. These are three of the larger implications that can be drawn from the information of the project. Now it is your turn. I encourage you as the reader to see what implications you can draw from this information.

Works Cited

Alter, George C., Myron P. Gutmann, Susan Hautaniemi Leonard, and Emily R. Merchant. “Introduction: Longitudinal Analysis of Historical-Demographic Data.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History Spring XLIII.4 (2012): 503-17. Web. 7 Feb. 2017.

Bashford, Allison. “Global Population | Books.” Columbia University Press. N.p., Jan. 2014. Web. 7 Feb. 2017.

Connelly, Matthew James. Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population. Cambridge, MA: Belknap of Harvard UP, 2008. Print.

“Free Xml Sitemap Generator.” Google. N.p., n.d. Web. 7 Feb. 2017.

Goldstone, Andrew, and Ted Underwood. “What Can Topic Models of PMLA Teach Us about the History of Literary Scholarship?” The Stone and the Shell. University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, 09 May 2014. Web. 7 Feb. 2017.

Healy, Kieran. “Philosophy Co-Citation Network, Force-Directed Layout.” Kieran Healy. Duke University, n.d. Web. 7 Feb. 2017.

Hoff, Derek S. The State and the Stork: The Population Debate and Policy Making in US History. Chicago: U of Chicago, 2012. Print.

Kaufman, Micki. “”Everything on Paper Will Be Used Against Me:” Quantifying Kissinger.” “Everything on Paper Will Be Used Against Me:” Quantifying Kissinger. Graduate Center of the City University of New York, n.d. Web. 7 Feb. 2017.

Lemov, Rebecca M. World as Laboratory: Experiments with Mice, Mazes, and Men. New York: Hill and Wang, 2005. Print.

Merchant, Emily K. “Introduction.” A Digital Reading of Twentieth-Century Demography. University of Michigan, n.d. Web. 7 Feb. 2017.

Nelson, Robert K. “Introduction.” Mining the Dispatch. University of Richmond, n.d. Web. 7 Feb. 2017.

Robertson, Thomas. The Malthusian Moment: Global Population Growth and the Birth of American Environmentalism. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 2012. Print.

Rohde, Joy. Armed with Expertise: The Militarization of American Social Research during the Cold War. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2013. Print.

ALL PHOTOS USED IN THIS POST ARE PROTECTED UNDER THE CREATIVE COMMONS LICENSE