The “Atlas of AI” by Kate Crawford comes at a pivotal time for the future of AI as it provides a comprehensive exploration of the societal impacts and ethical considerations surrounding artificial intelligence (AI). At a time when AI technologies are rapidly advancing and becoming deeply integrated into various aspects of our lives, understanding their implications is crucial for policymakers, technologists, and the general public alike. Through its detailed analysis and critical insights, the “Atlas of AI” serves as a timely guide for navigating the complex landscape of AI and its implications on human rights, socioeconomic inequalities, and sustainability.

The second chapter of the book shows how artificial intelligence is made of human labor. Crawford argues that we need to understand the influences of the past intersection of labor and automation and the current experiences of workers with AI to guide what the future of labor looks like. The author illustrates the connections between current AI development practices and the history of labor exploitation based on efficiency, asymmetries of power, and deception. An anchoring element for the chapter includes detailed depictions of workers’ experiences from the author’s visit to one of Amazon’s current fulfillment centers.

Through the other chapters, Crawford provides examples of how labor is seen as an input device of which systems seek to extract the most value. Narrations provide thorough depictions of the experiences of the workers at one of Amazon’s current fulfillment centers as well as at other factories around the world. You can feel the stress from the urgency and pain from the aching joints of the workers in these narratives.

In chapter two, Crawford crisscrosses through time to look at efficiency and its connection to technologies associated with time and surveillance. The historical elements contain references to Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and capitalist economic systems along with the usages of technologies like calculating machines and clock time. This is reinforced through descriptions of Charles Babbage’s work with workplace automation and the meat-packing industry in Chicago in the 1870s. More recent elements include Google’s TrueTime and algorithmic scheduling systems. Examining these elements provides insight into the complex relationship between economic theories, technological advancements, and labor dynamics throughout history.

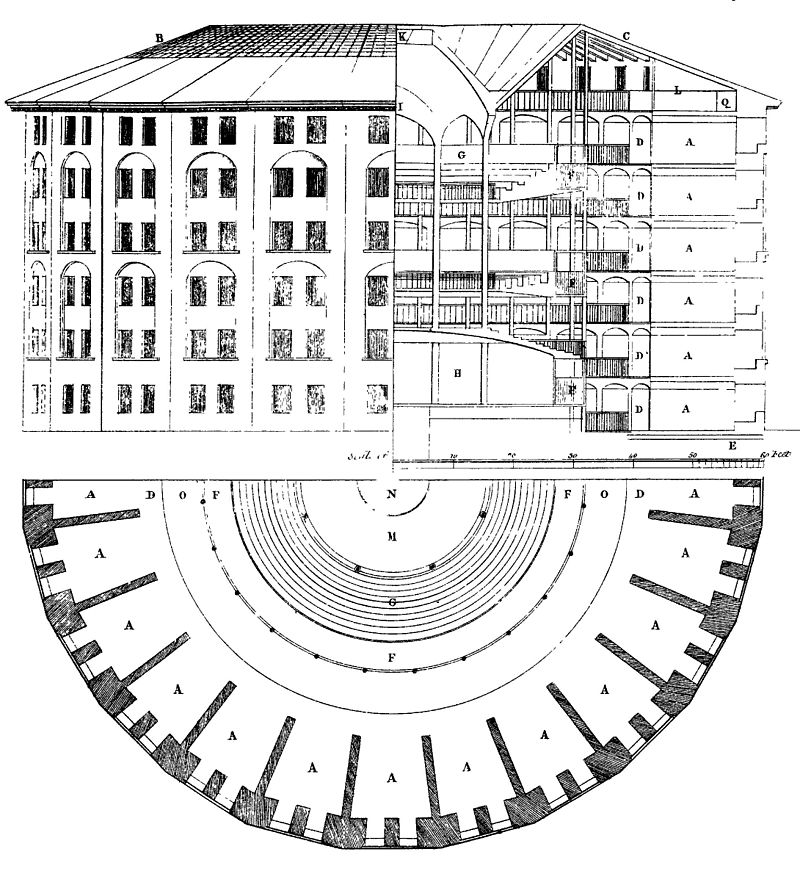

Crawford reviews various technologies, systems, and terminologies that have been used to control employees and create asymmetries of power. The first grouping concerns surveillance. The historical elements of surveillance come in the form of physical surveillance technologies including inspection houses in industrial manufacturing, panopticons, watch towers used in prisons, and overseers on plantations. Today’s digital surveillance shows up in the form of time clocks, machine-vision inspection systems, and productivity tools with metrics like productivity rates and countdown timers that will report slow progress.

The conditions for workers in these AI supported systems include underpayment for labor, requirements to perform repetitive tasks, operating in non-ergonomic environments, and at times working with trauma inducing material. Additionally, Crawford points out terminology like the master-slave metaphor that is pervasive in technology fields and still being used in Google’s TrueTime protocol. And while there has been movements to address this term as well as several others, there is still no consensus on standards across industries (Conger, 2021; Knodel & Oever, 2022; Landau, 2020).

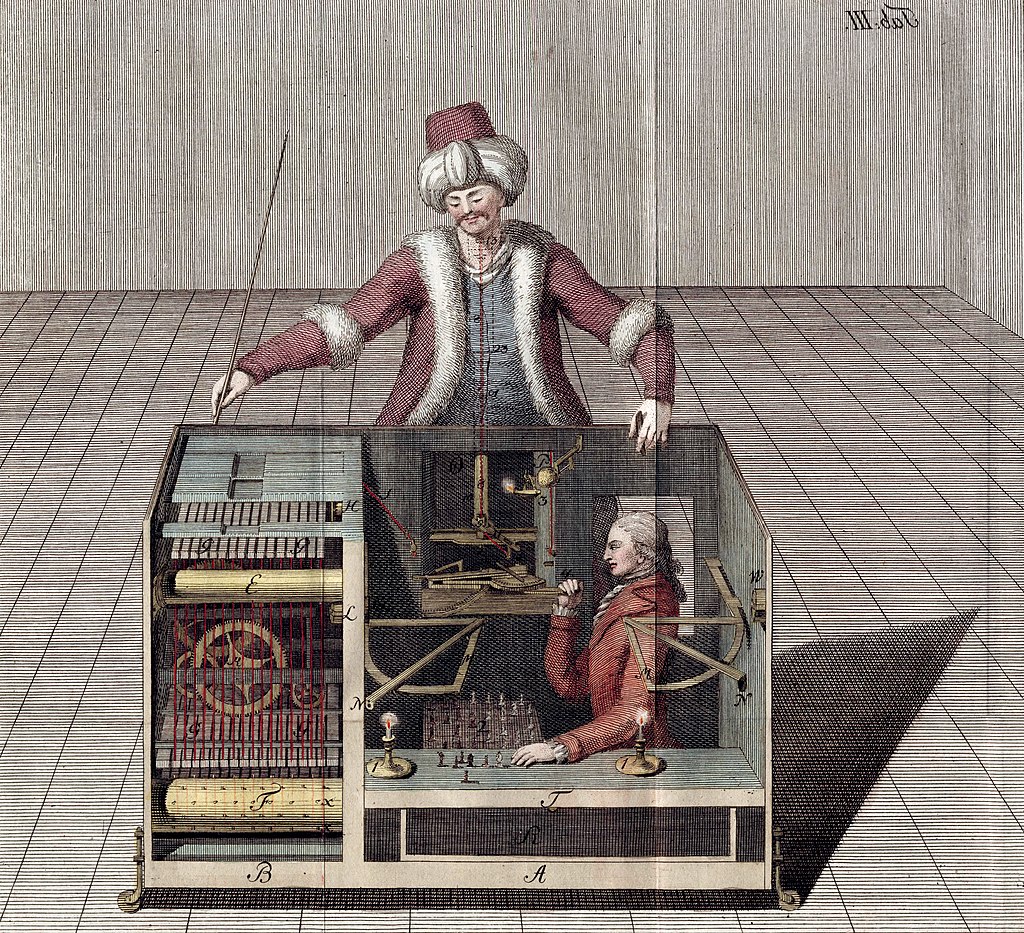

The third practice, deception, is based on the need of companies to give the appearance of successful AI services at a low cost. The author weaves stories about deceptions connected to Mechanical Turks and fauxtomation. Crawford describes the original Mechanical Turk, an illusion machine that showed a mechanical person playing chess while a person was hidden within a cabinet. Amazon used this term, Mechanical Turk, for its crowdwork platform that uses AI to open up meticulous and monotonous tasks to cheap global labor forces. The second practice is fauxtomation, which is the process of pushing repetitive work to the customer like the use of self-checkout systems in stores. These illusions of automation illustrate the complexities and ethical dilemmas inherent in contemporary labor practices facilitated by AI.

While reading the chapter, I first thought that the information was nothing new as my earlier education was in business schools and the history of automation was part of many courses. Then stepping back and talking to others, I realized that this history isn’t common knowledge and how important this chapter is as a foundation from which all of us can move forward from. By understanding the behaviors that have been instilled in society around labor and what elements will need to change, a different future of AI is possible.

While the author mentions the impact of AI on office-based workers, there is an opportunity to enhance the connection. Middle-class professionals are experiencing additional consequences. For example, the process of applying for jobs has been revolutionized and not always in a more helpful way. The enhanced AI job application systems allow for increased tracking of applications for both the employee and employer. However, bias against women was found in Amazon’s experimental hiring toot (Dastin 2022) or applicants can “spam” job listings with the click of a button “to apply to all”.

And while surveillance is an issue for office workers, it is not just surveillance by others but also the surveillance by themselves. Crawford discusses Foucault in refence to the panopticon, I wondered about Michael Foucault’s concept of “Governmentality”. Foucault used this term to describe how individuals and populations can be led to govern their own conduct themselves, through their own will (Foucault, 2010). And a different perspective on labor comes from Tom O’Reilly that suggests that AI programs are “ … workers, and the programmers who create them are their managers.” (O’Reilly, 2017).

If there is a second volume of this chapter, I would find it useful to have a section on asymmetric power relations in connection to the global division of labor and to explore the history of experiences of labor and AI in non-US countries. The global division of labor for AI systems is reflected in the lower paid jobs in data production hubs like those in Ghana, Kenya, or South Africa while the higher paying software engineer roles are in the US (Werthner et al., 2024). Since this book has been published there has been more awareness about this labor exploitation.

A specific example of this awareness was the creation of the International Network on Digital Labor (INDL) in 2019. This organization brings together researchers, students, union leaders and policymakers to discuss the linkages between work, algorithmic governance, and automation, and corporate culture in the platform economy (INDL, 2019). As there are data production hubs in various African countries, a specific conference on The Digital Labor Perspectives from the Middle East and Africa was created to discuss issues related to digital labor in that region (INDL-MEA, 2024).

In the second chapter on labor, Crawford provides a foundation for understanding the socioeconomic ramifications of the linkages of AI and labor. Through an analysis of the current AI development practices and the history of labor exploitation based on efficiency, asymmetries of power, and deception, the author demonstrates that labor is viewed as just a factor in production and a resource to be extracted. To have a different future, it is imperative to understand the labor conditions for workers and connection points with AI. By contextualizing AI within broader societal, economic, and historical narratives, we can see the possible implications for the future of labor and society.

References

Conger, K. (2021, April 13). ‘Master,’ ‘Slave’ and the Fight Over Offensive Terms in Computing. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/13/technology/racist-computer-engineering-terms-ietf.html

Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press.

Dastin, J. (2022). Amazon Scraps Secret AI Recruiting Tool that Showed Bias against Women *. In Ethics of Data and Analytics. Auerbach Publications.

Foucault, M. (2010). The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979 (First Edition). Picador.

INDL. (2019). INDL: International network on digital labor. https://endl.network/indl/

INDL-MEA. (2024). INDL-MEA Conference. https://www.indl.network/

Knodel, M., & Oever, N. ten. (2022). Terminology, Power, and Exclusionary Language in Internet-Drafts and RFCs (Internet Draft draft-knodel-terminology-09). Internet Engineering Task Force. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-knodel-terminology-09

Landau, E. (2020, July 6). Tech Confronts Its Use of the Labels ‘Master’ and ‘Slave.’ Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/tech-confronts-use-labels-master-slave/

O’Reilly, T. (2017). Managing a workforce of Djinns. In T. O’Reilly, WTF?: What’s the Future and Why It’s Up to Us. HarperCollins Publishers. https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/wtf-whats-the/9780062565723/text/nav.xhtml

Werthner, H., Ghezzi, C., Kramer, J., Nida-Rümelin, J., Nuseibeh, B., Prem, E., & Stanger, A. (Eds.). (2024). Introduction to Digital Humanism: A Textbook. Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-45304-5